Some Of My Experience About Linking C/C++ On Linux

I bought my first CSAPP in my freshman year at university. I barely read it, until two years later when I lost it and had to buy a new one. I still remember that the one of the most tough chapters to me is “Linking”. After graduating, the most challenging problem I’ve ever met in my c++ programming life is build system (e.g., CMake). And almost everything about build system is about linking. In this article I would like to share some experience that I’ve boiled down in my daily work. I would like to talk about both static library and shared library, the dependency between different libraries, and some interesting things that can only be done through the dynamic linking.

All the following content is based on Linux. I use CMake as the build system, and sometimes I will use compile/link command directly.

Create a static library and a shared library

Assume we have a c++ source file foo.cc. And we are going to build a library libfoo and provide it to other engineers. The first step is to compile the source and result in an object file. We use -fPIC as we will build a shared library later.

g++ -fPIC -c foo.cc -o foo.o

In the next step, we will create a static library and a shared library with foo.o. We use two commands to create them respectively.

ar rcs libfoo.a foo.o # static

g++ -shared -o libfoo.so foo.o # shared

The command we use to crate a static library is ar instead of g++. In fact, the static library is just an archive of the object files. We pack many object files together, which result in a static library. Shared library is quiet different from static library. But today we are not going to delve into any tech specification of ELF, Position Independent Code (PIC), PLT and GOT. Dynamic linking is very difficult, but luckily we can use it in the real-world programming without knowing every details of these stuff.

Now we can create an executable which links against the library we created before. It might be a main.cc that contains an invocation to a function which defined in libfoo.

g++ -o main main.cc libfoo.a

So far it’s very simple. I specified the static linking here because I want to introduce dynamic linking later. And we need to be aware of that we combined compile and link into one single command, but actually there is a intermediate step which creates main.o for main.cc. In the main.o there is a reference to the foo’s symbol, but this symbol is not defined in main.o.

One definition rule

There is an “One definition rule” in the C++ standard, which requires non-inline non-template functions, classes/structs, variables can only have one definition in the whole program (forgive me if I’m not being accurate, I am not a language lawyer). On a lower level, such rule give us a guarantee that in most scenarios, wherever we call a same name (after mangling) “target” in a program, we will eventually go to the same symbol (same address likewise). Two or more strong symbols (just ignore weak symbol here) with same name cannot coexist in one ELF file (executable and shared lib) or one object file, otherwise an compiler/linker error will occur.

void base() {}

void base() {}

int main() { base(); }

We can also separate two base() definitions to different translation unit, which won’t change the outcome. For example, by given foo.cc

#include "foo.h"

void base() {}

void foo() { base(); }

and bar.cc

#include "bar.h"

void base() {}

void bar() { base(); }

and main.cc.

#include "foo.h"

int main() { foo(); }

If we try to use the following commands to compile them together, then an error will occur when execute the last line, which is a same error as before.

g++ -c foo.cc -o foo.o

g++ -c bar.cc -o bar.o

g++ -o main main.cc foo.o bar.o

However, if we change to build our main by linking against libfoo and libbar, we will be surprised that the error disappear! Let’s do this with the following commands.

g++ -c foo.cc -o foo.o

g++ -c bar.cc -o bar.o

ar rcs libfoo.a foo.o

ar rcs libbar.a bar.o

g++ -o main main.cc libfoo.a libbar.a

We can use nm command to verify that there is only one base() symbol in the main. In order to figure out what happened here, we need to explore the behavior of linker.

Static linking order

We can build a mental model to help us understand how does linker work on the object files and the library files. Assume there is a symbol set E which contains all the symbols that will be packed into the executable file. Linker scans the input file in the order of the arguments are passed. If the incoming file is an object file, then linker will put all the symbols of this file into E. However, if the incoming file is a static library (actually, linking against a shared library is quiet similar here, later we will find it), then linker will only pick the “useful” symbols into E. Linker also maintains a set of undefined symbol, we denote it by U. It contains all the symbols that are referenced in E but for which the definition have not been found so far. If the incoming library provides some definition of the symbols within U, then these symbols will be picked into E, and meanwhile be removed from U. When linker completes the scanning, it will check both E and U: Every symbol in E must be distinct, and U must be empty. If the former constraint is violated, linker will complain “duplicate symbols” error. And if the latter constraint is violated, linker will complain “undefined symbol” error.

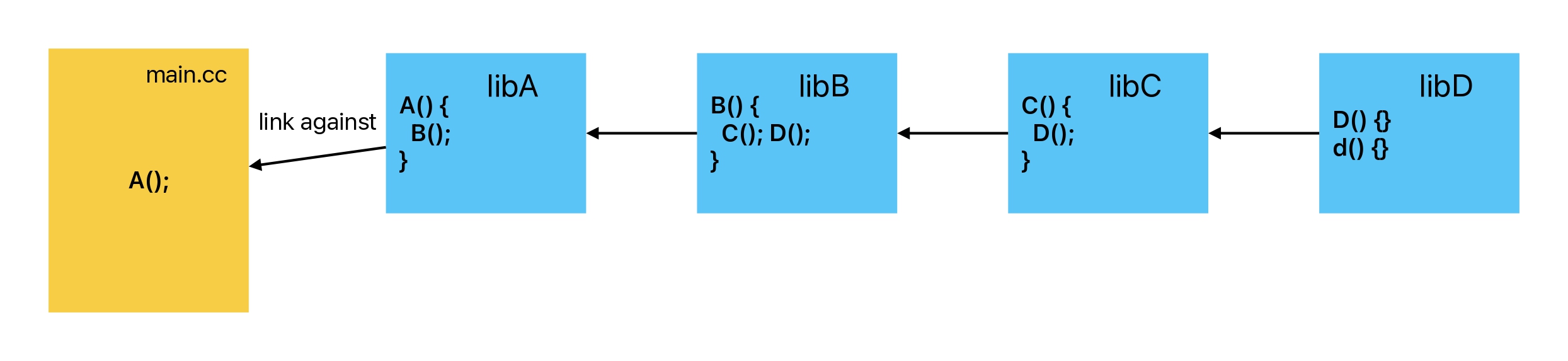

The rule of how linker deal with the libraries can help us avoid duplicate symbols error, but it requires programmer to manually maintain the dependency order among different libraries. The following picture illustrates an executable (source file main.cc) and its four dependency libraries. Although each library is an independent file (.a or .so), some of them reference the symbols that are not defined by themselves. For example, libA uses B(), which is defined in libB. libD is the only library that doesn’t rely on others (d() has nothing to do with D(), it is just named in lowercase by coincidence.)

We can compile this executable through g++ -o main main.cc -lA -lB -lC -lD, while the order we pass libraries to linker is exactly the order which illustrated by the picture. If we use static linking, then the executable file will contain the symbols of A(), B(), C, D(). d() will not be within, because it is not referenced by other codes. We cannot change the order of libraries. For example, if we put libC before libB, then when linker scans libC, C() will be ignored as it hasn’t been used. Finally, linker cannot find the definition of C() and complains “undefined symbol” error.

Maintaining the dependency order is not only the programmer’s burden when using the command line. It also matters when we using the CMake. We have to be aware of the order of libraries that be declared in target_link_libraries.

add_executable(main main.cc)

target_link_libraries(main PRIVATE A B C D)

Sometimes, one symbol might be provided by two libraries, and our executable has to link against both of them. If there is no dependency between them, then we can change their linking order to determine which library shall provide this symbol. Such mechanism sometimes can help us deal with the “diamond dependency” problem in CMake. I will introduce this in next chapter.

Having said that, at the end of this chapter, I want to point out an annoying fact that we can archive two object files which contain the same name symbols into a static library (such problem is not going to happen in the shared library). And by default linking against a library like this won’t lead a “duplicate symbol” error. Only one of the two symbols with the same name can remain in the executable, and another will be removed during the linking. But how do we know which one is the one that is used by the executable? There is no good way to know it or control it. And there is no error appear during the whole process either. But still we can determine if a library contains the duplicate symbols with the help of some symbol inspecting tools, such as nm or objdump. Here is an example of the usage of nm.

$ nm -C libfoobar.a

foo.cc.o:

0000000000000007 T foo()

0000000000000000 T base()

bar.cc.o:

0000000000000007 T bar()

0000000000000000 T base()

Libraries dependency in CMake

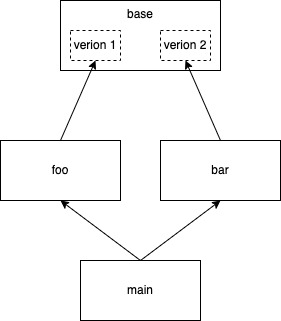

Let’s start from a CMakeLists.txt demo. The following scripts construct several static libraries, and an executable which is dependent on them. I create a duplicate library base2. it is not a real-world case, but I want to use it to simplify the circumstance that one library has two versions. This is a diamond dependency circumstance, foo relies on the base of version 1, and bar relies on the base of version 2. And finally, executable main relies on both foo and bar.

add_library(base base.cc)

add_library(base2 base.cc)

add_library(foo foo.cc)

add_library(bar bar.cc)

target_link_libraries(foo PUBLIC base)

target_link_libraries(bar PUBLIC base2)

add_executable(main main.cc)

target_link_libraries(main foo bar)

The following picture demonstrates the dependency that constructed by these CMake scripts.

We have more than one question need to figure out in this circumstance. The first thing is that we can use target_link_libraries on a static library target in CMake. That is, we can make a static library “link against” another library. And what is the effect? The answer is, nothing would happen to this library itself. When building libfoo.a, linker will not merge anything from libbase.a. libfoo.a is totally distinct to libbase.a. If libfoo.a references any symbol which is defined in libbase.a, the symbol would keep undefined. However, in CMake, when we add foo into other targets’ dependency, the dependency of foo will be propagated. Therefore, main is also dependent on base although we didn’t put base into main’s target_link_libraries list.

We can confirm the linking command by specifying VERBOSE=1 when building the target.

mkdir build && cd build

cmake ..

VERBOSE=1 make

The possible output when linking the main is

[100%] Linking CXX executable main

/usr/bin/cmake -E cmake_link_script CMakeFiles/main.dir/link.txt --verbose=1

/usr/bin/c++ CMakeFiles/main.dir/main.cc.o -o main libfoo.a libbar.a libbase.a libbase2.a

As we can see, main is actually linked against all four libraries. And the linking order is the order that we declared in target_link_libraries. The direct dependency always precedes the indirect dependency. In the direct dependency, foo precedes bar, and in the indirect dependency, base precedes base2 because base’s dependent foo precedes base2’s dependent bar. Now assume that base and base2 are two different versions of a same library. If we want to use the newer version in out executable, we can simply put bar before foo.

In fact, I am of the opinion that using target_link_libraries on a static library target is unnecessary at all. Such practices sometimes only cause us more trouble. It’s not easy to sort out the indirect dependency order when we have imported too many libraries. It might be easier to specify all the dependency manually.

Dynamic linking

We will discuss dynamic linking in this chapter. But right now I want to give some conclusion directly. It’s somehow like the appendix to the previous chapter. In contrast to the static linking, if we link a shared library against another static library, the symbols from that static library will be merged into .so, by default, however, only the symbols that be used in the shared library will be merged. We can also link a shared library against another shared library, such behavior won’t merge anything but propagate the dependency. But unlike static library, the indirect dependency of shared library not only exists in CMake, it comes to the OS level. We can use ldd command to inspect it. For example, the GNU’s c++ standard library libstdc++.

$ ldd /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libstdc++.so.6

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007ffc8ed97000)

libm.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libm.so.6 (0x00007fc9918f8000)

libc.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 (0x00007fc99141f000)

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007fc9919df000)

libgcc_s.so.1 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libgcc_s.so.1 (0x00007fc9918d8000)

We found that libstdc++ is dependent on libc. The c++ standard library relies on c standard library, it’s not surprising at all, is it?

Now, let’s replace out diamond dependency demo with a dynamic linking version. At first, I will use raw commands instead of CMake scripts, it helps us to understand how linker works at the low level.

g++ -c -fPIC base.cc -o base.o

ar rcs libbase.a base.o

g++ -shared -fPIC foo.cc -L. -lbase -o libfoo.so

g++ -shared -fPIC bar.cc -L. -lbase -o libbar.so

g++ -o main main.cc -L. -Wl,-rpath=. -lfoo -lbar

In the AI era, we can ask ChatGPT to explain the unfamiliar scripts and commands. But I still want to explain these commands in more detail. We have seen -shared and -fPIC before, and now we have -L. -L is used to specify a directory so that linker can lookup the library files. (By the way, -I is used to specify a directory which to lookup the including headers.) And what is -Wl,-path?, actually it should be divided into two parts. -Wl means the following (no space, but we can use comma) arguments should be passed to linker as the options. So, -Wl,-rpath=. means that we pass -rpath=. to linker. -rpath= is used to add a directory to the runtime library search path. Is it in conflict with -L? The answer is no, while static linking only need to search the libraries during compile/link time, dynamic linking need to search the shared libraries in both compile/link time and runtime. When we upgrading a program, it is possible to upgrade only the shared libraries without changing the executable itself. The shared libraries lookup directory used in runtime has nothing to do with the directory which specified by -L. The ldd command lists all the shared libraries that required by the specified ELF. It shows the paths where we can find these shared libraries.

$ ldd main

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007ffc851f2000)

libfoo.so => ./libfoo.so (0x00007ff370473000)

libbar.so => ./libbar.so (0x00007ff37046e000)

libc.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 (0x00007ff370287000)

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007ff37047f000)

If we link main without -Wl,-rpath=, later when we run our program, dynamic linker cannot find foo and bar by default. But this problem can be addressed by using LD_LIBRARY_PATH to specify the lookup directories when running the program.

$ ldd main

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007ffd98fec000)

libfoo.so => not found

libbar.so => not found

libc.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 (0x00007f27af729000)

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007f27af917000)

$ ./main

./main: error while loading shared libraries: libfoo.so: cannot open shared object file: No such file or directory

$ LD_LIBRARY_PATH=. ./main # if we want to specify multiple paths, separate them by `:`

So far, we have statically linked foo and bar against base. The symbols in libbase.a are merged into libfoo.so and libbar.so (only the symbols we actually need). Therefore, these two shared libraries contain the same name symbols that come from libbase.a. However, by default, all the symbols reference by the shared libraries will participate the global relocation which performed by dynamic linking in runtime. The symbol firstly found by dynamic linker will be used globally. Like I said before, such behavior is quiet similar as static linking. Since libfoo.so precedes libbar.so in the default loading order, out program will use the symbols of base that provided by libfoo.so.

It reveals by using the shared libraries, we can hook functions or variables without recompiling the program. It is commonly used when we want to hook some system calls or replace the default malloc implementation. On linux, malloc(3) is provided by libc by default, and our program is linked against it dynamically. Therefore, we can use LD_PRELOAD to load other malloc library (such as tcmalloc or jemalloc) before loading libc.

Despite I made the shared libraries link against another static library in this demo. I personally don’t suggest to do such thing in the real-world programming. In most scenarios, packing different libraries together is not a good idea. There is another potential trap we should be aware it that when we link against a static library, by default we will only pack the symbols that we currently need. Let’s say that libbase.a contains the definition two functions: base() and derive(), but neither foo nor bar use the latter one. If we need to invoke derive() in our executable, then we have no choice but statically linking libbase.a directly as we cannot find its definition in neither libfoo.so nor libbar.so. As a result of that, the symbols that come from same libraries are separated into different places in out program: some are within the executable file, others are with in the shared libraries. I suppose such result is counterintuitive. As an alternative, we can give --whole-archive to linker (by using -Wl,--whole-archive) to enforce linker merge the whole static library into the ELF. But it might cause other problems.

Anyway, what I recommend is if we decide to use dynamic linking, then use it as much as possible. The following CMake scripts will build all libraries dynamically. The executable main will not be directly dependent on libbase.so, but libfoo.so does (as well as libbar.so).

add_library(base SHARED base.cc)

add_library(foo SHARED foo.cc)

add_library(bar SHARED bar.cc)

target_link_libraries(foo PUBLIC base)

target_link_libraries(bar PUBLIC base)

add_executable(main main.cc)

target_link_libraries(main foo bar)

Isolability of the shared library

When we are dealing with the diamond dependency, making the whole program use the same “base library” is usually a good choice. We have already known how to do this in the previous chapters. However, sometimes we may encounter version conflicts. That is, for example, we have two libraries and we need to use them both. Both libraries are dependent on protobuf, but one has to use an older version while another has to use a newer version. In such scenario, our program has to contain two protobuf libraries of different versions. It’s impossible in static linking, because duplicate symbols are not allowed in an ELF. Somehow we can bypass this restriction with dynamic linking.

In the previous chapter, wa said that by default all the symbols referenced by the shared library will participate a runtime global relocation, even if the symbol’s definition has been provided by the same shared library. If we can bind the references to the definition within the same library, we can make different libraries use their own symbols. Still, I will use a demo about base, foo, and bar to demonstrate it. First, we have base.cc

#include <iostream>

void base() {

#if defined(VERSION_2)

std::cout << "Version 2\n";

#else

std::cout << "Version 1\n";

#endif

}

and foo.cc

#include "foo.h"

void base();

void foo() { base(); }

and bar.cc

#include "bar.h"

void base();

void bar() { base(); }

and finally, main.cc

#include "bar.h"

#include "foo.h"

int main() {

foo();

bar();

}

We use following commands to build our program.

g++ -c -fPIC base.cc -o base.o

ar rcs libbase.a base.o

g++ -c -fPIC base.cc -o base.o.2 -DVERSION_2

ar rcs libbase.a.2 base.o.2

g++ -shared -fPIC foo.cc -L. -l:libbase.a -o libfoo.so

g++ -shared -fPIC bar.cc -L. -l:libbase.a.2 -o libbar.so

g++ -o main main.cc -L. -lfoo -lbar -Wl,-rpath=.

What will the program output? The answer is definite: “Version 1\nVersion 1”. We linked foo before bar, so the symbol within the libbase.a is adopted by the whole program. If we exchange the order between foo and bar, the program would output “Version 2\nVersion 2” instead. But obviously, none of them are what we want. We want our program to print “Version 1\nVersion 2”.

Let’s change the commands to build the two shared libraries. And rebuild it again.

g++ -shared -fPIC foo.cc -L. -Wl,-Bsymbolic -l:libbase.a -o libfoo.so -Wl,-Bdynamic

g++ -shared -fPIC bar.cc -L. -Wl,-Bsymbolic -l:libbase.a.2 -o libbar.so -Wl,-Bdynamic

This time, the program will output the content which is same as our expectation. No matter how do we change the order between foo and bar, the output would be same: “Version 1\nVersion 2”. It’s because we use -Bsymbolic to bind the references to the symbols within the same libraries. Please note that we have to use -Wl,-Bdynamic at the end of the command to restore the default linking behavior, so that it can links other basic libraries such as libstdc++ normally. (We also have another option -Bstatic but we are not gonna use it.)

It’s seems prefect now, but what if we want to invoke base() directly in out executable? Would we invoke version 1 or version 2? The definition will be provided by either foo or bar, depending on who comes firstly. This is still not pleasant enough. A better choice is to make base private from foo and bar. Which means the symbols comes from base will be hidden from libfoo.so and libbar.so. And when we invoke base() in the executable, we link another base library directly. That is, we will have three different definition of base() in our program, and they can coexist peacefully without bothering each other.

There are several ways to hide symbols from a shared library. And my favorite one is by using the version scripts. We don’t need to change our codes, an additional file is used to configure the visibility. The hidden symbols will not participate the global relocation, so they can be regarded as “private”.

Before introducing the version scripts, we need to know how to inspect whether a symbol is hidden or not. Once again, welcome to our old friend, nm. There are lots of documents about nm on the internet. Briefly speaking, nm uses a character to denote the symbol type. If the character is lowercase, the symbol is usually local (hidden), otherwise it is global.

# the unrelated output has been removed

$ nm -C libfoo.so

0000000000001129 T foo()

0000000000001135 T base()

The symbol type of both foo() and base() is T, which means they are both global. We want to hide base() while foo() remain globally. Please be aware of that with -C option, nm shows the demangled symbol name. But we need to use the original symbol name in the version script. Under the current Itanium C++ ABI rules, the corresponding symbol name of foo() is _Z3foov. And bar() corresponds to _Z3barv, accordingly.

Now we can crate a version script file, name is as foobar.map

{

global:

_Z3foov;

_Z3barv;

local:

*;

};

Again, we change the commands and rebuild the program.

g++ -shared -fPIC foo.cc -L. -l:libbase.a -o libfoo.so -Wl,--version-script=foobar.map

g++ -shared -fPIC bar.cc -L. -l:libbase.a.2 -o libbar.so -Wl,--version-script=foobar.map

The output of nm shall become

# the unrelated output has been removed

$ nm -C libfoo.so

0000000000001129 T foo()

0000000000001135 t base()

In order to verify the effect, we can add an invocation in our main.cc.

#include "bar.h"

#include "foo.h"

int main() {

base();

foo();

bar();

}

If we didn’t hide the symbols, our program should be built. But since we hide the base from the both shared libraries, linker would be unable to find the symbol definition for the executable.

$ bash build.sh

/usr/bin/ld: /tmp/cc4a1RYg.o: in function `main':

main.cc:(.text+0x5): undefined reference to `base()'

collect2: error: ld returned 1 exit status

At the end, I would like to give a full example of how to use these techniques in CMake.

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.13)

project(my_demo)

add_compile_options(-fPIC)

add_library(base base.cc)

add_library(base2 base.cc)

target_compile_definitions(base2 PRIVATE VERSION_2)

add_library(foo SHARED foo.cc)

add_library(bar SHARED bar.cc)

target_link_libraries(foo PUBLIC base)

target_link_options(foo PRIVATE -Wl,--version-script=${CMAKE_CURRENT_SOURCE_DIR}/foobar.map)

target_link_libraries(bar PUBLIC base2)

target_link_options(bar PRIVATE -Wl,--version-script=${CMAKE_CURRENT_SOURCE_DIR}/foobar.map)

add_executable(main main.cc)

target_link_libraries(main foo bar base) # change to base2 if you want to use version 2 in main.cc